Payrolls rose by a much-more-than-expected 353,000 in January as the jobless rate held steady at 3.7 percent. In ours X threadsCEA highlights some of the key factors in today’s report, including:

- The three-month moving average of wage growth is now 289,000.

- Over the past two months, payroll employment was revised up by a total of 126,000.

- The youth labor force participation rate increased to 83.3%.

- Average hourly earnings rose 0.6%.

In this post, we address the question that many of those who follow this data likely had in mind when they clicked over to the BLS website this morning and saw the large number of jobs: what explains the sudden jump? ! Monthly data is noisy, and while a shortfall relative to expectations of today’s magnitude is unusual, it can happen. But it is also the case that the US economy has consistently defied expectations, with stronger-than-expected growth and faster-than-expected declines in inflation. In other words, there’s more to this strong working relationship than “who knows?!”

Keep it calm

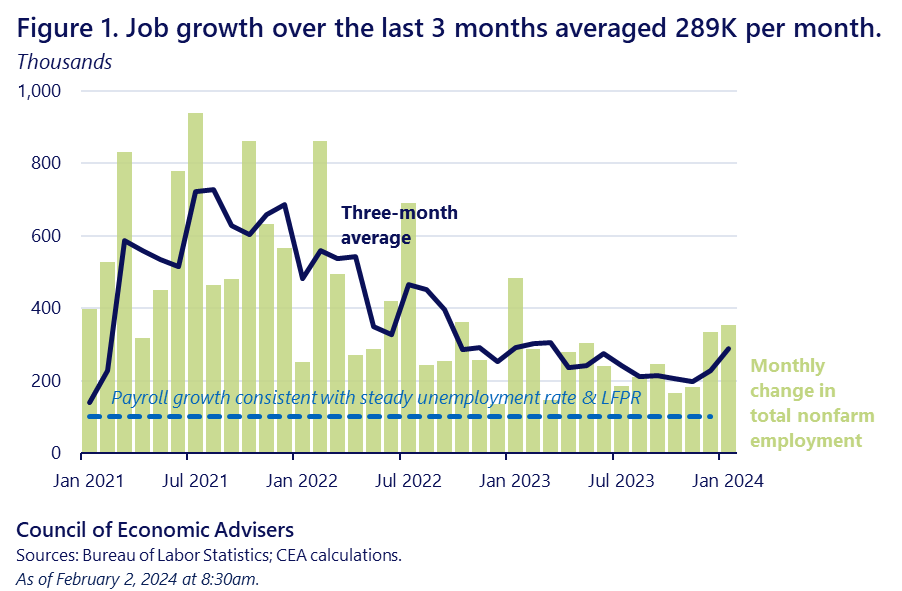

A standard practice in CEA is to increase the signal-to-noise ratio by averaging over longer periods, which smooths out some of the jumpiness that occurs in monthly data. Figure 1 below shows the 3-month average of monthly gains – 289,000 from November to January – cuts the bips and bops in the monthly bars. However, even with the easing, we see an increase in recent job gains, although they are well below the three-month average of 483,000 in January 2022. As shown in the figure, in a peaceful way The job growth trend has slowed recently. In fact, the January jobs signal is consistent with other recent economic results, including strong Q4 2023 GDP growth.

Let’s face it: the labor market, along with the rest of the US economy, has defied expectations for a while now.

This upside surprise is largely consistent with a wide variety of recent indicators. The 353,000 jobs number in January follows an upwardly revised gain of 333,000 for December. Job gains were also widespread across the labor market, with gains in goods, services and public sector jobs. Just under two-thirds of private sector industries added jobs last month, a higher rate of distribution than the 2011-19 average. Wage growth was also strong last month, up 0.6 percent for the month and 4.5 percent over the year. While we don’t have CPI inflation for January yet, in December, it was 3.4 percent year-over-year (well below December’s 4.3 percent annual wage gain). Part of January’s strong wage growth could have come from weather-driven compounding effects: if total hours in every major industry were the same in January as they were in December, wage growth would have been about 0.1 percentage point lower in January.

The unemployment rate has been below 4 percent for 2 years in a row, the best such record since the 1960s. Real GDP also surprised in growth last quarter and throughout the year (see Figure 1 here that shows how GDP real at the end of 2023 was just under $1 trillion higher than expected, according to the Blue Chip forecast at the end of 2022).

The CEA has long focused on the effects of persistently low unemployment growth through the consumer spending channel. The combination of strong job growth, rising nominal wages and slower inflation has led to solid gains in aggregate compensation, which, as shown in Figure 3 here, are highly correlated (0.78) with real consumer spending (70 percent of nominal GDP).

Each month can jump either way

While the points above focus on the labor market and broader macroeconomic fundamentals, care must be taken not to over-interpret one-month data, especially outliers (big upside or downside surprises compared to expectations). The monthly job numbers reflect many sensible adjustments, expertly applied by the BLS. The Bureau adjusts for seasonal variations, to ensure that labor market analysts are observing economy-oriented data versus seasonal hiring and layoffs (eg, the sharp increase in teenage employment in the summer is a phenomenon seasonal, not a sign of any new economic trend). To capture employment changes caused by new firms entering the economy and old firms leaving, they estimate a birth/death model. Once a year, they adjust payroll job numbers based on an employment record.[1] Monthly revisions have also been made to the previous two payroll reports. For example, in today’s report, the November and December jobs numbers were revised up by a cumulative 126,000.

In any given month, these adjustments, as well as random sampling variability or even disruptive weather (the January snowstorms led to an increase in people who were out of work or working fewer hours), can bias the number of jobs up or down relative to the underlying trend. For this reason, CEA assesses broad trends and tries to understand the many connections between different macroeconomic variables from many different reports, as well as the impacts of our policies. Doing so reveals a strong US economy, consistently supported by a very solid labor market that is generating real gains in wages. President Biden’s investment agenda is also clearly attracting large amounts of private capital to support the construction of manufacturing plants (construction employment has increased by 774,000 since the President took office.)

So while we wouldn’t hang our hat on any monthly number, this morning’s data clearly reveals the continued strength of the US labor market, which is at the heart of the current recovery and Bidenomics!

[1] In fact, the annual review of the standard is reflected in today’s payroll report. Hiring for March last year was revised up to 266,000 jobs, down about -22,000 jobs in the month from April ’22 to March ’23.

#January #Employment #Report #Explaining #big #heady #surprise #CEA #White #House

Image Source : www.whitehouse.gov